Art, faith and listening

Interview with Orev Reena Katz

Par Camille Buffet

Orev Reena Katz is an ordained Hebrew Priestess and a Registered Psychotherapist working in Ontario and British Columbia. Combining the two fields of psychotherapy and spiritual care, Orev has provided spiritually informed psychotherapy for individuals who are dealing with incarceration, and youth struggling with involvement in extremist movements, as well as their families and circles of care. Before dedicating their time to spiritual care, art took a large part of Orev’s life as she spent many years working as an artist. We met Orev casually on a Monday morning where she delved deeper into her professional activities today, what it means, and how art participated in their development as a human being.

You offer one-on-one counselling for individuals who are dealing with incarceration. Can you tell us more about what you do, and how you came to offer such services?

My background is in spiritual care and psychotherapy. Spiritual care is a newer term that’s used in the field that was formerly known as chaplaincy. It’s not coming from a specific faith tradition, but a general sense of how important human spirituality is to our health and our whole being. It’s incorporated and woven through the practices of psychotherapy.

I came to that work through many years of social justice organizing, and community arts practice. When I turned 40, I became a little bit unsatisfied with how the art system functions, especially creative practices that were attempting to make social change. I turned towards some of my community of priestesses that I was training with at the time. Many of them were doing a program called CPE, Clinical Pastoral Education, which is essentially a placement in an institution, it could be a hospital, it could be a hospice, it could be a prison, it could be a food bank, where spiritual care is necessary in practice.

Over time, I was able to work in federal prisons in several different contexts and with people of all genders and sexualities. I came to learn that this was really the right approach for me in terms of making a difference and changing the violence of our world in terms of police brutality, in terms of the prison system, and really trying to learn and practice restorative and transformative justice principles. So that’s what I do, it’s a holistic practice.

Your work is spiritually informed and based in Judaism. What does spiritual care mean to you? How does it influence your work with individuals who are familiar with violence?

Definitely my work is rooted in Jewish principles. I have a lot of challenges and struggle with my faith as well. The way Judaism is now discussed, in terms of global politics, is really problematic for me, and really different than how I take our ancestral tradition and the teaching. For me, the traditions of my ancestors are helpful, are resonant for me and are rich and alive, are traditions I like to share.

However, I don’t come to my work, sort of fronting that Jewish theology, which I like to call radical or critical Jewish theology. It’s not traditional Jewish theology. And someone like me, you know, a queer person who has been doing Palestine solidarity work for decades, and who’s extremely feminist, is not your traditional Jew, for sure. Having said that, I wouldn’t work with a person unless they themselves requested that. I wouldn’t work with the person from that place. It’s more like my own backpack of materials of teachings, of approaches. To answer your second question, we have a lot of variety of strategies for talking to people, and helping them help us understand what meaning is for them, what makes your life meaningful. When we talk about folks who perpetuate violence, a lot of times their meaning making has turned inside out or been forwarded or somehow been rejected so many times that they have internalized that meaninglessness. Spiritual care can show up and say “when did that start in your life?”. We are born into believing we are meaningless, we’re not, so what were the conditions in your life that taught you your life doesn’t matter, and you don’t deserve to be happy? And really, that takes trust, one couldn’t ask that on the first session. But drilling down from that place is so much more effective, I find, than starting with the behavior. Because the behaviors are what’s in front, but the thinking and the belief about self is what’s behind that. It’s a very delicate, very gentle journey.

« When we talk about folks who perpetuate violence, a lot of times their meaning making has turned inside out or been forwarded or somehow been rejected so many times that they have internalized that meaninglessness. »

Your approach is based on transformative justice. Can you explain what transformative justice is? How can it allow us, as individuals and as a society, to view violence and harm in a new perspective? What I want to say is that transformative justice comes from a variety of racial and indigenous approaches to dealing with harm, and community. It’s built from the ground up in community, mostly by folks who have been directly impacted for generations by the colonial injustice system. These are folks who have known in their bones and their blood that it does not work, that those systems are actually designed to maintain white supremacy and they’re not designed to address harm. And yet, we’re human, we make mistakes, and we cause harm. So what do we do when harm happens?

« We’re human, we make mistakes, and we cause harm. So what do we do when harm happens?»

Transformative justice came out of an impulse to protect BIPOC people from being harmed by the police and to still address the harm that has occurred. And it really came out of many different feminist intersectional movements in the States, queer and trans movements, sexual violence in particular is harming our communities, has harmed our community for generations, and we actually want to start dealing with that from a place of empowerment and not a place of disempowerment. The principles of transformative justice are contagious, because they essentially say: no one is disposable. There is no one in our community who deserves to be locked up. They say, our community has resources, enough to hold harm when it happens. And they say harm comes from a world we live in that is profoundly violent.

The acronym BIPOC

BIPOC stands for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. Pronounced “bye-pock,” this is a term specific to the United States, intended to center the experiences of Black and Indigenous groups and demonstrate solidarity between communities of color. The term “BIPOC” is more descriptive than people of color. It acknowledges that people of color face varying types of discrimination and prejudice. Additionally, it emphasizes that systemic racism continues to oppress, invalidate, and deeply affect the lives of Black and Indigenous people in ways other people of color may not necessarily experience. It reinforces the fact that not all people of color have the same experience, particularly when it comes to legislation and systemic oppression Source: YWCA, “Why we use the term BIPOC”. Accessible at https://www.ywcaworks.org/blogs/ywca/wed-04062022-0913/why-we-use-bipoc

And what transformative justice really points to is, “how has violence played out in this person’s life to the point where they then cause harm?” And how much time and investment do we have as a community to hold capacity for that? How willing are they to change? Who in their life is going to consistently show up for them? Transformative justice does not work with the criminal justice system at all, it works separately. It’s all in the community.

Transformative justice and restorative justice

In the first edition of Mag 404 published two years ago, the team dedicated a whole article to restorative justice. We visited the CSJR, le Centre de services de justice réparatrice, and interviewed Estelle Drouin, a jurist specialized in human rights. The CSJR is also a partner of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts where they offer art-therapy workshops for people who have been touched by violence or heinous acts. You can find more about it on the Mag 404’s website at https://404mag.org/ !

Before offering spiritually informed psychotherapy, you were quite active as an artist. What were your practices? According to you, how can art be a driver for reintegration?

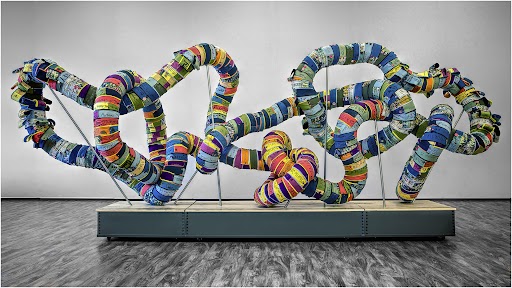

When I was working full time as an artist, I was very lucky to be part of a community of artists who were invested in art. We would always ask questions about what is its function? How is that possible? Is it an illusion? Is Art really just for the elite? What is the human need to create? And does that actually support social change? What I was interested in is the process of change.

I became very interested in what it meant to speak, to transmit, and to receive conversation, information. What happens in the body? Is there resonance? On a material level does our skin absorb? Do our bones absorb? Do our eyeballs understand what it is? How do we create empathy? Because in almost every social justice movement, the request at its core is, listen to us, understand our experience. How do we understand? That was sort of my big artistic question. That’s why it was so natural for me to move into therapy and spiritual care, because it’s a very similar set of questions.

« I became very interested in what it meant to speak, to transmit, and to receive conversation, information.»

With great assistance, I was able to set up a series of workshops, from a variety of traditions, but mostly indigenous, that were about ancestral practices, whether it was beading, or painting or other pieces, people would come and just learn how to do that thing. They might already know how or it might be their first time or their thousandth. And in the space, there was creation happening, there was always food, there was always teaching, there was always music. And there was always an open-door policy. You can come, you can go, you can stay for the whole session, or you can leave. And when we first gathered, we always made shared agreements, how do we want the space to feel, what do we want to do here? Who do we want to be? And that openness created a sense of belonging for all of us. It was profound, because it helped me realize and remember that for many people, there’s no place in their life that looks or feels that way.

During your educational path, you have completed a Master of Fine Arts at New York City’s Parsons School of Design where your thesis explored listening and empathy. Since this year’s edition of our magazine is “giving yourself a voice,” we are curious about your take on the act of listening. Can you explain what your thesis consisted of and what we can learn from your research?

I don’t know how much there is to learn from it. This is going back a decade. I was really lucky in my graduate school years, because the timing coincided with the Occupy Wall Street movement. Essentially, the goal was to dismantle capitalism. And that’s what people were talking about all the time, everywhere. It was a really interesting time.

There was a thing that would happen at Occupy Wall Street, which was called the People’s mic. Because it wasn’t a regular demonstration, it was just like an encampment. And there would be these spontaneous public things that one individual or a group started. And they didn’t have microphones, or megaphones. They didn’t have the equipment, technology, or the equipment necessary to really project their voices.

So this thing got invented and emerged, because of the conditions of that movement, where one person spoke, and then waves of people repeated what they said, so that people in the back could hear, and it’s incredible. I mean, if you YouTube, like Angela Davis, Occupy Wall Street, it was awesome. What happened in their bodies was that they were actually in real time, speaking Angela Davis’s wisdom. Not just for themselves, but actually for other people to hear. It would be these waves of word, waves of motivation, of prophecy, of anger, of hate, of joy, coming through the crowds.

That became the central activity that I was trying to understand through my thesis. For me it was about raising voice, projecting voice, sharing voice, being heard, and the amazing human ingenuity of creating a new technology through our voices. Without microphones, not only it was not a problem, it actually was a benefit to that movement.

Considering your life experience, do you have any piece of advice for our readers regarding how we can be better listeners for each other and better care providers for our community?

I work on my listening skills every day, I am not an expert. And it’s much easier for me to listen well. A really great question, process and practice for me has been, “how do I need to be resourced to show up with calmness and non-reactivity?” Because I feel like reactivity is the antithesis to building relationships, it shuts us down. It gets our nervous system into a place of defensiveness instead of “oh, I’m curious, tell me more about that.”

And the question for me then became “how did I have that curiosity?” And is it possible to help others come to that? There are methods and techniques, there’s active listening, or you simply speak back, there are ways of listening for feelings.

And then things like mindfulness or meditation, where you spend time with your own feelings, offering yourself compassion as a model for how you want to be with others. Those are some really key tools that have helped me and my clients.

« I feel like reactivity is the antithesis to building relationships, it shuts us down. It gets our nervous system into a place of defensiveness»